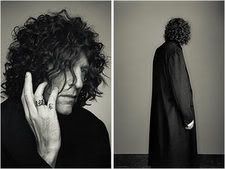

Howard Stern - American Pioneer

Love him or hate him, Stern is a true pioneer

Radio star all but invented reality programming, freewheeling discourse

By James Sullivan

MSNBC contributor

Updated: 2:56 p.m. ET Dec. 14, 2005

Great American pioneers: Lewis and Clark, Charles Lindbergh, Rosa Parks … Howard Stern?

The talk-radio blowhard who deals in relentlessly off-color humor, celebrates bodily secretions with a four-year-old’s glee and surrounds himself with a misfit cast of self-professed drunks, stutterers, retards and angry dwarves?

This may horrify those already inclined to believe the country has fallen, culturally speaking, so far that it can’t get up, but: Yes. Howard Stern, a pioneer. Emphatically, yes.

Even long before he signed that colossal contract — reportedly in the neighborhood of $500 million for five years — to bring his outrageous shtick to the new medium of satellite radio, Stern was already a bona fide American pioneer. And not just as an entertainer, someone who brings laughs, however puerile the material, to an estimated 12 million people (20 million at his peak) each weekday morning. The original big-name shock jock is a tireless crusader for free speech, one of the basic tenets, of course, of Western democracy.

Sure, he’s going to Sirius (“Eh-eh-eh,” as they’ve been calling it on the old show, where he is forbidden to mention his new employer) for the money. More than that, however, he is defecting to make a very big point, after clashing one too many times with the titans of corporate radio and the Federal Communications Commission, which has made Stern the most heavily fined broadcaster in the agency’s history. Howard gets paid to say whatever’s on the tip of his tongue — every word of it — and he does not take kindly to anyone who would wash it out with soap.

Paying for his humor

He’s been fined for joking about masturbating to a picture of Aunt Jemima; for having a guest who played piano with his genitals; for a graphic conversation with the guy responsible for the Paris Hilton sex tape.

“I disapprove of what you say,” as the famous quote has it, “but I will defend to the death your right to say it.” Often attributed to the French philosopher Voltaire, the line’s origins are uncertain. It may as well have been Howard, who can’t stand the French, anyway.

That tenacity has earned Stern a loyal, ardent following poised to follow him into a whole new format. He’s the Pied ****ing Piper of potty mouth, for **** sake.

“Love him or hate him, you can’t deny his success,” Ed Bradley declared in a surprisingly sympathetic profile on “60 Minutes” earlier this month. In the mid-‘90s, after building an empire for Infinity Broadcasting with blanket syndication, Stern declared himself the King of All Media. He launched a cable TV version of his radio program, published two runaway bestsellers and starred as himself in a feature film. He even ran for governor of New York, aptly enough, on the Libertarian Party ticket.

“Let someone see the full range of emotions,” Stern told Bradley, describing his basic broadcasting philosophy. At its core, that philosophy is an ongoing critique of the rigorous self-censorship that guides typical media presenters, be they talk show hosts, anchors, topical panelists — the full range of yakkers who address the American public over the airwaves and through the broadband connections.

For his absolute devotion to his own id, Stern is often compared with the late comedian Lenny Bruce. He’s also a kind of media-age, R-rated Holden Caulfield, still nurturing the unfettered impulses of adolescence while mocking the pervasive “phoniness” of American public life.

Stern’s move to satellite lends instant legitimacy to the developing medium. In that world, he’s already a D.W. Griffith, a Henry Ford. (Besides revolutionizing an industry, Stern shares with those predecessors an uncomfortable propensity for race-baiting.)

The inventor of reality programming

The list of cultural diversions that have arrived in the wake of Howard’s ascendance is long, and remarkably broad. Without Stern, we might have much less emphasis on fatuous celebrities. There would be no gross-out reality TV as we know it, much less suburban acceptance of strip-club culture, no Drudge Report or “Crank Yankers” or Triumph the Insult Comic Dog.

A world without some of that dogged commitment to vulgarity might sound to some like an unattainable heaven. But a world without Howard would also, in all likelihood, be a world without our contemporary brand of freewheeling discourse, a world without both Fox News’ Bill O’Reilly and “The Daily Show”’s Jon Stewart. Outrage, from whichever side of the social or political spectrum, is Stern’s stock in trade — “there’s a general distrust, a lot of fear,” he told “60 Minutes” — and he has helped make it a national pastime.

There are times when Stern’s verbal fearlessness borders on surprising profundity. Often these are times of crisis, such as on September 11 or after the L.A. riots. Because he feels no compulsion to distance himself from his gut reaction, he can come across at moments like those, amazingly enough, as a lone voice of reason.

But the bottom line isn’t his occasional minuet with sincerity, or even that gargantuan salary. The bottom line is, Howard’s funny. Not funny all the time; sometimes not funny for hours on end. But he’s using a variation on the Black Power fist as the logo for his new venture. This from a man who readily admits that his trademark indignation comes from growing up one of the few remaining white kids in an increasingly black Long Island town.

In the words of one notorious segment from the Stern show archives, “It’s Just Wrong.”

And that’s what makes it funny.

James Sullivan lives in Massachusetts and is a regular contributor to MSNBC.com.

© 2005 MSNBC Interactive

© 2005 MSNBC.com

URL: http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/10454035/from/RSS/

Radio star all but invented reality programming, freewheeling discourse

By James Sullivan

MSNBC contributor

Updated: 2:56 p.m. ET Dec. 14, 2005

Great American pioneers: Lewis and Clark, Charles Lindbergh, Rosa Parks … Howard Stern?

The talk-radio blowhard who deals in relentlessly off-color humor, celebrates bodily secretions with a four-year-old’s glee and surrounds himself with a misfit cast of self-professed drunks, stutterers, retards and angry dwarves?

This may horrify those already inclined to believe the country has fallen, culturally speaking, so far that it can’t get up, but: Yes. Howard Stern, a pioneer. Emphatically, yes.

Even long before he signed that colossal contract — reportedly in the neighborhood of $500 million for five years — to bring his outrageous shtick to the new medium of satellite radio, Stern was already a bona fide American pioneer. And not just as an entertainer, someone who brings laughs, however puerile the material, to an estimated 12 million people (20 million at his peak) each weekday morning. The original big-name shock jock is a tireless crusader for free speech, one of the basic tenets, of course, of Western democracy.

Sure, he’s going to Sirius (“Eh-eh-eh,” as they’ve been calling it on the old show, where he is forbidden to mention his new employer) for the money. More than that, however, he is defecting to make a very big point, after clashing one too many times with the titans of corporate radio and the Federal Communications Commission, which has made Stern the most heavily fined broadcaster in the agency’s history. Howard gets paid to say whatever’s on the tip of his tongue — every word of it — and he does not take kindly to anyone who would wash it out with soap.

Paying for his humor

He’s been fined for joking about masturbating to a picture of Aunt Jemima; for having a guest who played piano with his genitals; for a graphic conversation with the guy responsible for the Paris Hilton sex tape.

“I disapprove of what you say,” as the famous quote has it, “but I will defend to the death your right to say it.” Often attributed to the French philosopher Voltaire, the line’s origins are uncertain. It may as well have been Howard, who can’t stand the French, anyway.

That tenacity has earned Stern a loyal, ardent following poised to follow him into a whole new format. He’s the Pied ****ing Piper of potty mouth, for **** sake.

“Love him or hate him, you can’t deny his success,” Ed Bradley declared in a surprisingly sympathetic profile on “60 Minutes” earlier this month. In the mid-‘90s, after building an empire for Infinity Broadcasting with blanket syndication, Stern declared himself the King of All Media. He launched a cable TV version of his radio program, published two runaway bestsellers and starred as himself in a feature film. He even ran for governor of New York, aptly enough, on the Libertarian Party ticket.

“Let someone see the full range of emotions,” Stern told Bradley, describing his basic broadcasting philosophy. At its core, that philosophy is an ongoing critique of the rigorous self-censorship that guides typical media presenters, be they talk show hosts, anchors, topical panelists — the full range of yakkers who address the American public over the airwaves and through the broadband connections.

For his absolute devotion to his own id, Stern is often compared with the late comedian Lenny Bruce. He’s also a kind of media-age, R-rated Holden Caulfield, still nurturing the unfettered impulses of adolescence while mocking the pervasive “phoniness” of American public life.

Stern’s move to satellite lends instant legitimacy to the developing medium. In that world, he’s already a D.W. Griffith, a Henry Ford. (Besides revolutionizing an industry, Stern shares with those predecessors an uncomfortable propensity for race-baiting.)

The inventor of reality programming

The list of cultural diversions that have arrived in the wake of Howard’s ascendance is long, and remarkably broad. Without Stern, we might have much less emphasis on fatuous celebrities. There would be no gross-out reality TV as we know it, much less suburban acceptance of strip-club culture, no Drudge Report or “Crank Yankers” or Triumph the Insult Comic Dog.

A world without some of that dogged commitment to vulgarity might sound to some like an unattainable heaven. But a world without Howard would also, in all likelihood, be a world without our contemporary brand of freewheeling discourse, a world without both Fox News’ Bill O’Reilly and “The Daily Show”’s Jon Stewart. Outrage, from whichever side of the social or political spectrum, is Stern’s stock in trade — “there’s a general distrust, a lot of fear,” he told “60 Minutes” — and he has helped make it a national pastime.

There are times when Stern’s verbal fearlessness borders on surprising profundity. Often these are times of crisis, such as on September 11 or after the L.A. riots. Because he feels no compulsion to distance himself from his gut reaction, he can come across at moments like those, amazingly enough, as a lone voice of reason.

But the bottom line isn’t his occasional minuet with sincerity, or even that gargantuan salary. The bottom line is, Howard’s funny. Not funny all the time; sometimes not funny for hours on end. But he’s using a variation on the Black Power fist as the logo for his new venture. This from a man who readily admits that his trademark indignation comes from growing up one of the few remaining white kids in an increasingly black Long Island town.

In the words of one notorious segment from the Stern show archives, “It’s Just Wrong.”

And that’s what makes it funny.

James Sullivan lives in Massachusetts and is a regular contributor to MSNBC.com.

© 2005 MSNBC Interactive

© 2005 MSNBC.com

URL: http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/10454035/from/RSS/

<< Home